1 July 2025

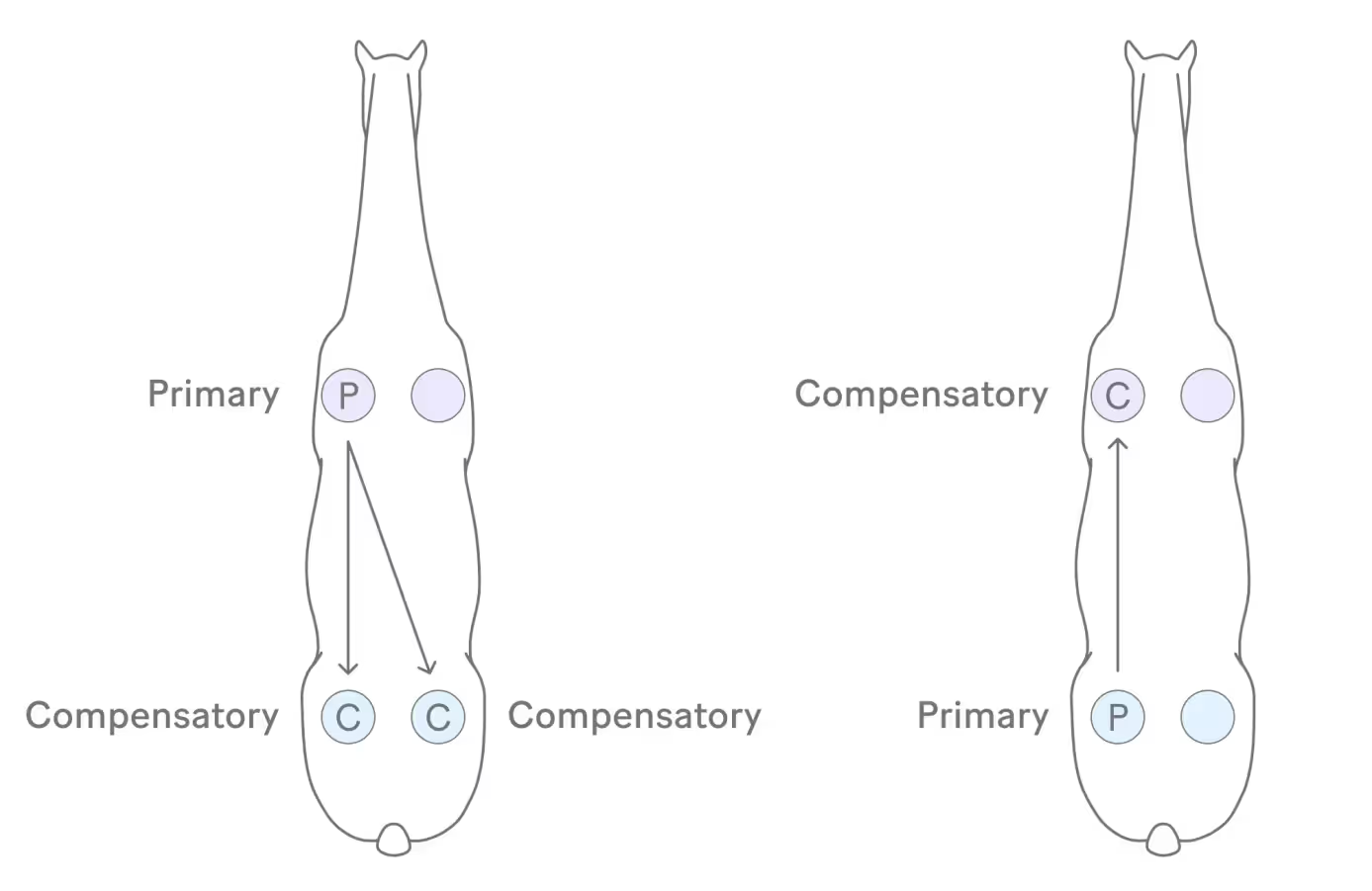

Horses with lameness issues often adapt their movement to ease discomfort, which can produce compensatory movement asymmetries. This means a primary lameness in a forelimb can cause asymmetries in the hindlimb and vice versa.

When a horse experiences pain in a limb, its primary method of pain relief is to reduce weight-bearing on that limb. This strategy creates a telltale sign when horses are trotted on a straight line:

However, diagnosing lameness is not as straightforward as that. In many cases, the horse may further adapt its movement to manage the pain caused by the primary lameness. This creates an additional layer of compensation.

The compensatory asymmetries follow certain patterns as the horse tries to redistribute its weight and lessen the load on the painful limb. A key diagnostic tool for veterinarians in recognising these patterns and identifying primary lameness is the "Law of sides" principle.

This is a well-researched principle. Simply put, when a horse experiences lameness or pain in one of its forelimbs, it tends to get a compensatory asymmetry from the diagonal hindlimb. In cases of hindlimb lameness, it tends to display a compensatory asymmetry from the ipsilateral (same-sided) forelimb. In addition, the direction of the trunk asymmetry, mainly the impact asymmetry, can be used to support the interpretation.

When a horse experiences lameness or pain in one of its forelimbs, it tends to compensate by changing the movement of the diagonal hindlimb. This often results in a push-off asymmetry from the diagonal hindlimb (C) and an impact asymmetry on the same-sided hindlimb (C). As a result, the horse's pelvis moves unevenly.

The trunk asymmetry can be used to further support interpretation of this pattern. In cases of primary frontlimb lameness, the trunk impact asymmetry is typically seen in the same direction as the head, supporting the interpretation that the pelvic asymmetry is secondary.

When a horse experiences hindlimb lameness, the resulting head nod may be misinterpreted as lameness in the forelimb on the same side (C). This head nod occurs as the horse tries to alleviate weight from the painful hindlimb by using its head as a counterweight. In instances of primary hindlimb lameness, the compensatory pattern observed in the head movement can be pretty pronounced. Clinicians should be mindful of working up the wrong limb.

In cases of primary hindlimb lameness, the trunk impact asymmetry is typically seen in the opposite direction as the head, supporting the interpretation that the head asymmetry is secondary.

Although the law of sides explains most of the compensatory patterns studied, there are still unusual patterns that are not fully understood. One of these patterns is the “head push-off pattern”. In this case, horses show a marked push-off asymmetry of the head without an impact asymmetry and with no further asymmetries on the pelvis. This unusual pattern might be associated with pain but it is still unknown if this represents a weight-bearing lameness, where horses try to unload the affected limb. Further assessment of the horse with a thorough clinical exam and assessment of motion under different conditions, such as longeing, often provides further insight into the origin of this asymmetry.

If you notice multiple asymmetries across various body parts, such as an asymmetry in the head and trunk, combined with one in the pelvis, or vice versa, it generally calls for extra caution in clinical interpretation. An asymmetry should always be interpreted in a broader clinical context and preferably against a baseline measurement of the horse's natural movement pattern at sound. It’s important to remember that asymmetry is not synonymous with weight-bearing or pain-induced lameness.

They are fairly common. In a recent study (Reed et al., 2020), of 1,224 horses presented for lameness evaluation, 56.6% of horses showed combined head and pelvis asymmetries, which were attributed in the majority of cases to compensatory asymmetries.

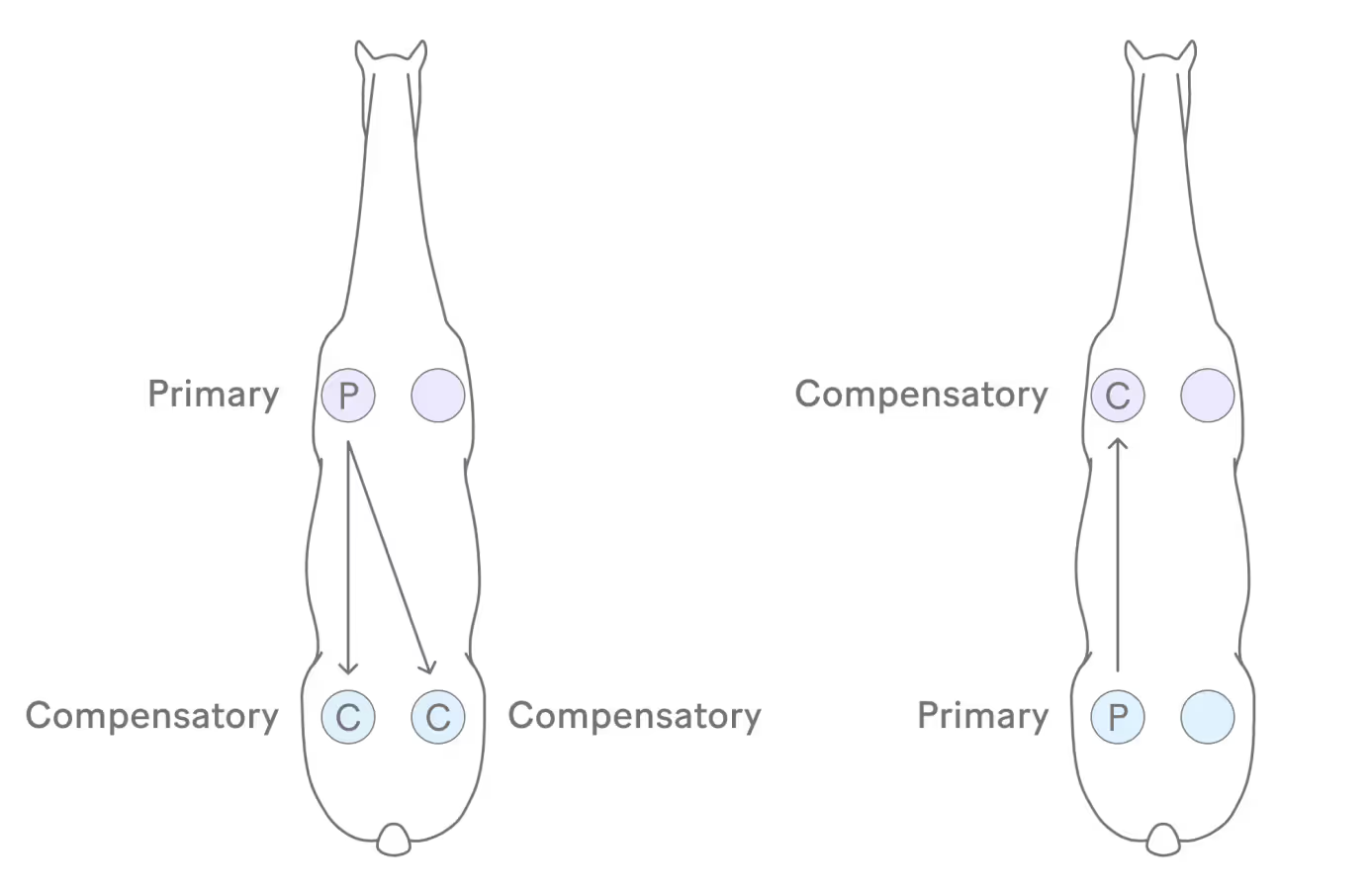

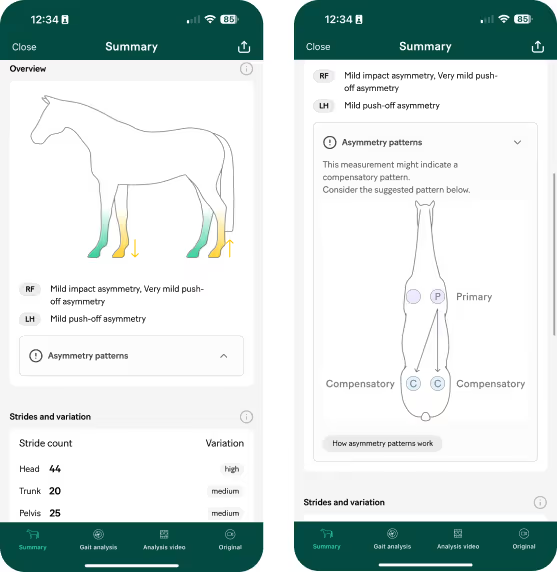

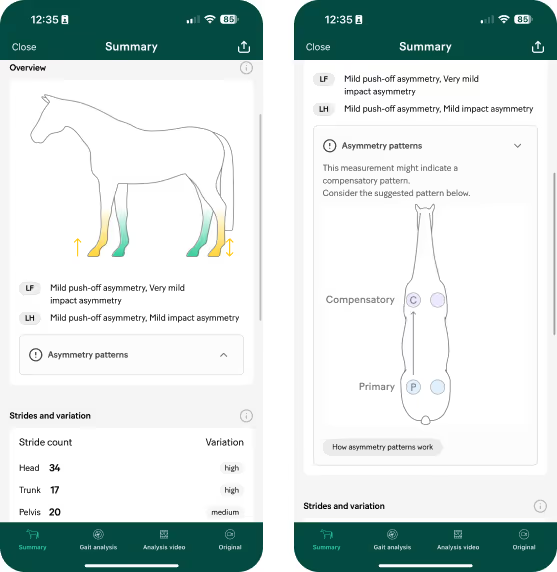

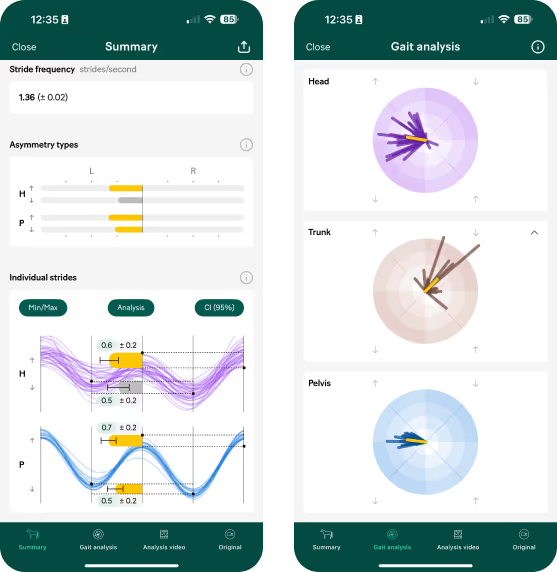

Sleip assesses the relationship between measurements of impact and push-off asymmetries in both the head and pelvis. Following pre-defined rules based on the principles of the law of sides, Sleip categorises a recording as exhibiting asymmetry patterns with potential compensatory components. Currently, the app flags the three most common compensatory patterns. Going forward, Sleip has the potential to recognise additional patterns based on aggregate data to enhance the collective understanding of compensatory mechanisms further.

Guus, a young Haflinger gelding used for recreational riding, presented with a gradual onset of low-grade lameness. Despite a period of rest, the lameness persisted without improvement.

Guus’s analysis results indicate a primary forelimb lameness accompanied by a typical compensatory diagonal push-off hindlimb asymmetry. In this case, you can see that the trunk impact asymmetry in the asymmetry vectors plot, has the same direction as the head, supporting the typical pattern of primary frontlimb lameness.

A diagnostic nerve block, an infiltration of the insertion of the suspensory ligament of the right front was performed. Following the block, both the primary lameness in the right forelimb and the compensatory asymmetry in the left hindlimb showed significant improvement. This confirmed that the left hindlimb asymmetry was indeed a compensatory response. A lesion of the suspensory ligament was confirmed by ultrasound.

In Guus's case, the diagonal hindlimb asymmetry could have been mistaken for a primary hindlimb issue if not carefully evaluated in conjunction with the forelimb lameness, supported by the trunk asymmetry data.

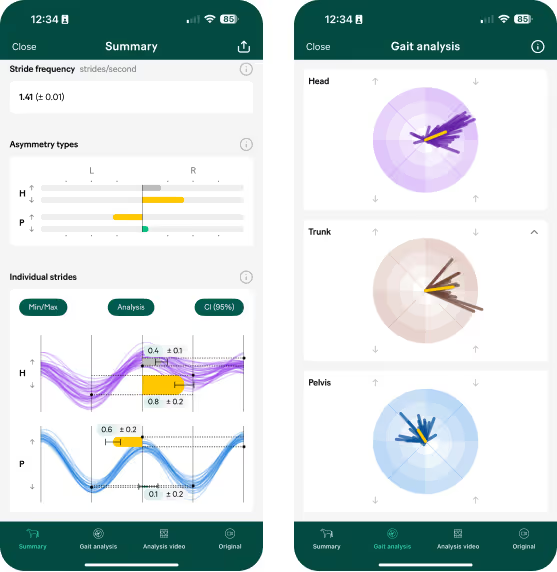

Fenix is a 12-year-old Dutch Warmblood owned by a riding school. He presented with a progressively worsening lameness on the right hind limb (RH). Notably, this lameness exhibited increasing asymmetry over time.

Fenix demonstrates a typical pattern of primary hindlimb lameness with a compensatory asymmetry in the ipsilateral forelimb. In this case, you can see that the trunk impact asymmetry in the asymmetry vectors plot points in the opposite direction to that of the head, supporting the typical pattern of primary hindlimb lameness.

This case illustrates that compensatory asymmetries, observed here in Fenix's left forelimb, can sometimes be as pronounced—or even more pronounced—than the primary lameness in the hindlimb. This can easily result in incorrect diagnostic procedures, such as blocking the wrong limb if the clinician interprets the head nod as a primary forelimb lameness rather than a secondary compensatory response.

When evaluating lameness, especially in cases involving subtle or low-grade presentations, it's crucial to consider the possibility of compensatory asymmetries. These can confound the origin of the primary issue, leading to potential misdiagnosis.