29 August 2024

Horses with lameness often adapt their movement to reduce discomfort. These compensations can lead to secondary asymmetries, meaning a primary issue in a forelimb may cause movement changes in the hindlimbs—and vice versa.

"These adaptations tend to follow recognisable patterns. One biomechanical principle that helps interpret them is the Law of Sides, which guides clinicians in diagnosing the root cause of the lameness", explains Filipe Bragança, Biomechanics Researcher and Product Manager at Sleip.

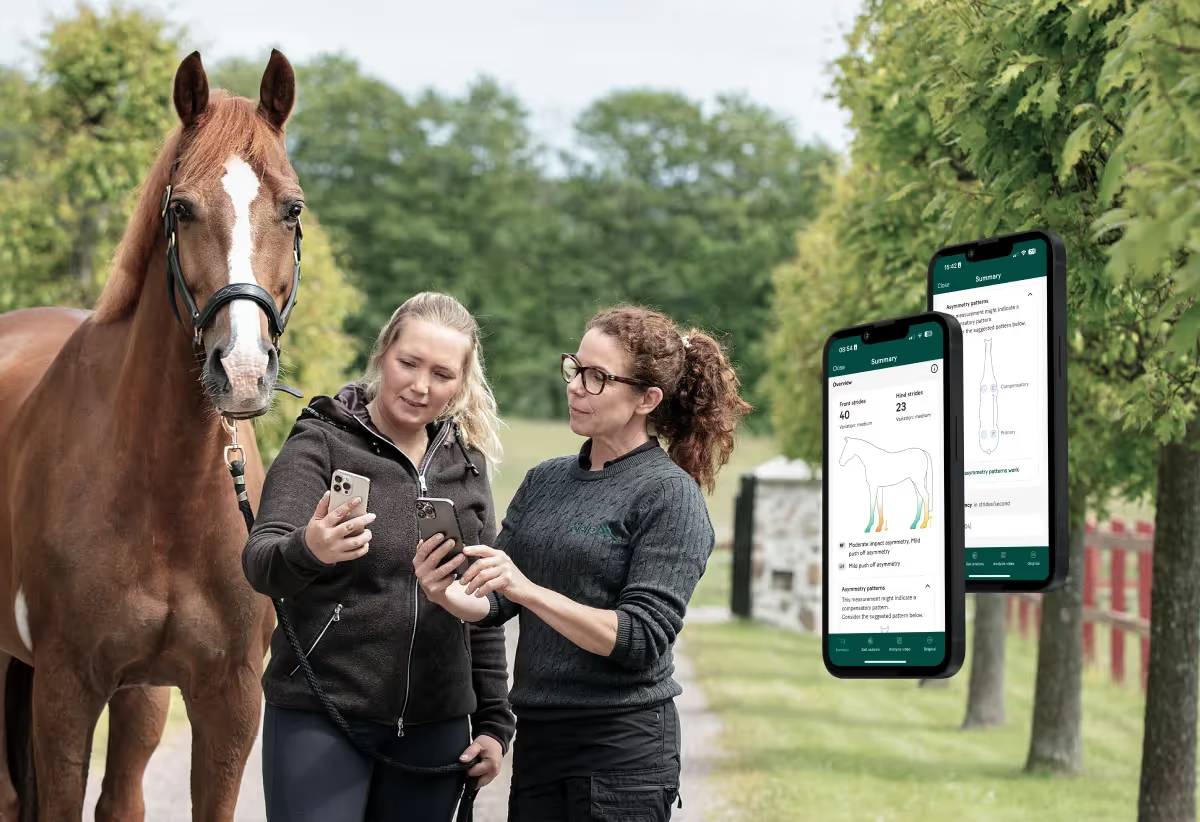

Building on this biomechanical principle, Sleip’s new feature analyses the relationship between impact and push-off asymmetries in both the head and pelvis. Recordings that match known compensatory patterns are automatically flagged—adding important clinical context during evaluations.

At launch, the app identifies the three most common compensatory patterns. As data continues to grow, Sleip will expand its capabilities — advancing the understanding of equine movement and enabling more informed decisions in lameness diagnostics.Want to learn more about compensatory patterns? Read the blog post.