4. Chronic OA and functional adaptation

Inside the joint

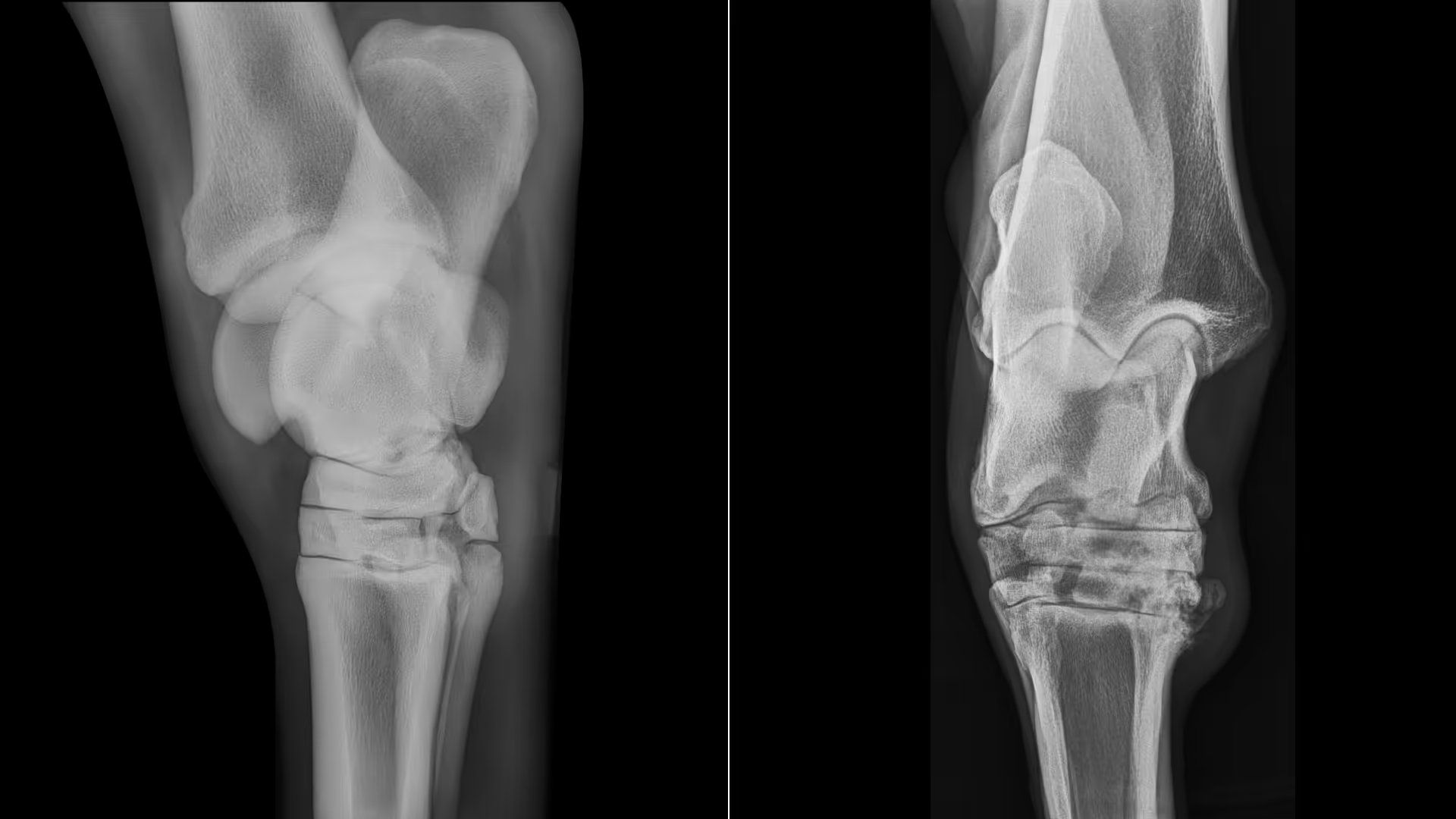

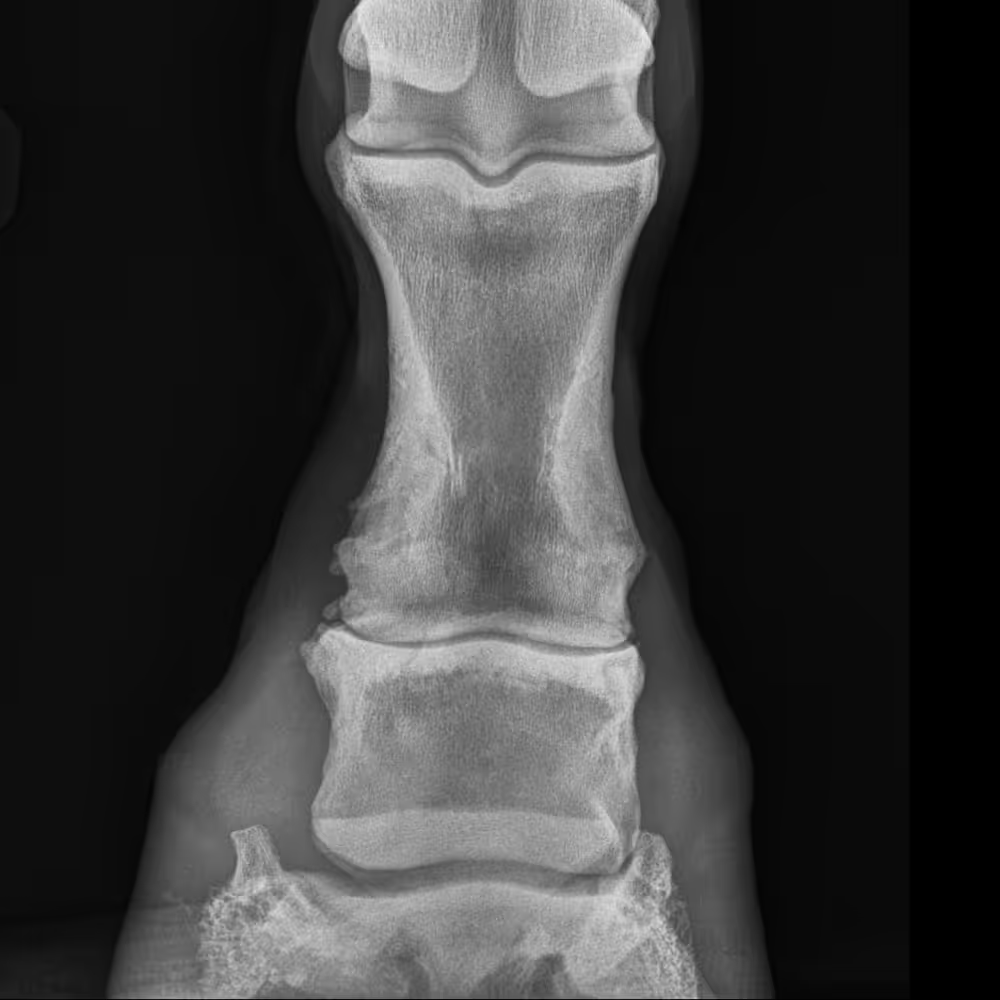

Advanced, irreversible changes with widespread cartilage loss, subchondral bone remodeling, and joint capsule fibrosis. Pain may now arise from multiple tissues, including bone and periarticular structures.

Clinical presentation

Persistent lameness, compensatory gait patterns, and declining function. However, pain level can vary widely and is not always proportional to the degree of joint change seen on imaging.

Management goal

Focus on long-term comfort, function, and welfare. Adapt management to the individual horse’s clinical response and quality of life

In summary

At this stage, the horse and its musculoskeletal system adapt to chronic pain and altered joint mechanics, often through compensatory movement patterns.